New England can be old fashioned, stodgy, even demure in some respects. These descriptors could also be applied to Boston's drum makers of the 1920s. Flying in the face of such generalizations is the appearance of this drum. In a cosmetic sense this instrument most definitely appears to be of its time. The sparkling gold wrap and faux gold hardware suggest this was not your average George B. Stone & Son drum. Even the exposed wooden areas of the counterhoops are painted gold lest any part of the drum be left ungilded. The overall impression is nearly garish.

While the entire visual aesthetic of this instrument is straight out of the roaring twenties to be sure, it is not so different from any other Master-Model produced by Stone in regards to construction and design. The old fashioned wooden hoops remain, as does the unorthodox method used to tension the heads which was conclusively obsolete by the late 1920s. The throw-off and butt plate are somewhat primitive too as was the case with all of Stone's hardware by the late 1920s and early 1930s.

|  |

What sets this drum apart of course is the brilliantly well preserved sparkling gold wrap. The wrap color is quite rich on this example showing very little visible signs of wear and fading. The sparkle pattern itself is very fine grained, closely resembling the wrapped finishes used by Leedy during the same time period. So as to pair with the shell, the hoops are also wrapped in matching strips with the remaining exposed wooden surfaces painted a similar hue of gold.

It is worth noting that George B. Stone & Son Catalog K (1925) makes no mention of wrapped finishes, only "Black De Luxe", "White De Luxe", and natural maple. Stone did however produce a small number of drums finished in pearl and sparkle wraps during the late 1920s and into the 1930s. Examples are known to exist in silver sparkle, red sparkle, white marine pearl, and black diamond pearl. By 1928 wrapped Master-Models are included on Stone price lists, and by 1932 price lists include a "Pyralin" Master-Model for $50.00, a significant increase over the white or black lacquer options priced at $40.00 and the natural finish at $35.00.

The hardware seen here is finished in what Stone cataloged as "Nobby Gold", a faux gold finish accomplished by plating the metal parts in brass before applying a final coat of clear lacquer to prevent tarnishing. The claws, nuts, and washers, which are steel, were first plated in nickel before receiving the brass plating. The lug posts are made from brass and did not need to be nickel plated prior to the brass plating and final lacquering. Catalog K describes Nobby Gold as being available "at small additional cost". Stone also claims that the finish "wears better than real gold and costs less". The former claim may be a case of advertising rhetoric, however, as wear does indeed occur over time and eventually rust begins to creep in.

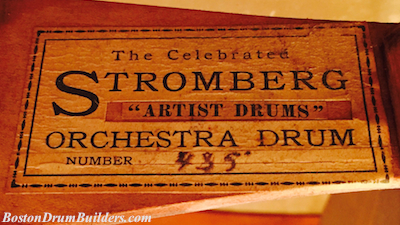

Labels and marking on this drum are consistent with those on other Master-Models. The badge installed here is a solid brass version of the usual Master-Model badge which commonly has a black enameled background. The four digit Stone serial number is both ink stamped onto the label, and firmly imprinted inside of the wooden shell. Stone discontinued the practice of date stamping sometime in 1925, so a specific date of manufacture can not be determined.

|  |

Interestingly, this drums features conflicting Master-Model numbers. Perhaps this was a special order which was moved along quickly through the factory. That would be one way to explain how numbered hoops could have been installed on a shell bearing a different Master-Model number.

|  |

Do you have a Stone Master-Model? I would love to hear about it! Feel free to send Lee an email anytime at lee@vinson.net. And a very special thanks to my friend Chris in Washington, DC for allowing his drum to be featured here!